Dr. Román González

BRCA1 was the first gene discovered, 30 years ago in 1994, whose mutations conferred a predisposition to developing breast cancer. It is the main cause of hereditary breast cancer. Carrying a harmful mutation in this gene confers a probability of up to 50% of developing breast cancer before the age of 50 and 90% throughout life, and it is also the most aggressive type, known as ‘triple negative’, for which there are no effective treatments. In addition, mutations in BRCA1 also predispose individuals to other cancers such as ovarian cancer and prostate cancer in men.

Today, women who carry BRCA1 mutations are advised to undergo preventive removal of their breasts and ovaries to avoid the onset of devastating cancer before the age of 50.

Over the last 30 years, countless studies and articles have been published on this gene. BRCA1 plays a role in repairing DNA damage, specifically in repairing double-strand breaks in DNA, through a mechanism called ‘homologous recombination’. Most radio and chemotherapy therapies seek to produce breaks in the DNA that tumour cells with this mutated gene cannot repair, causing them to die. However, through alternative mechanisms, these cells develop resistance to these treatments, rendering them ineffective and making these tumours much more aggressive.

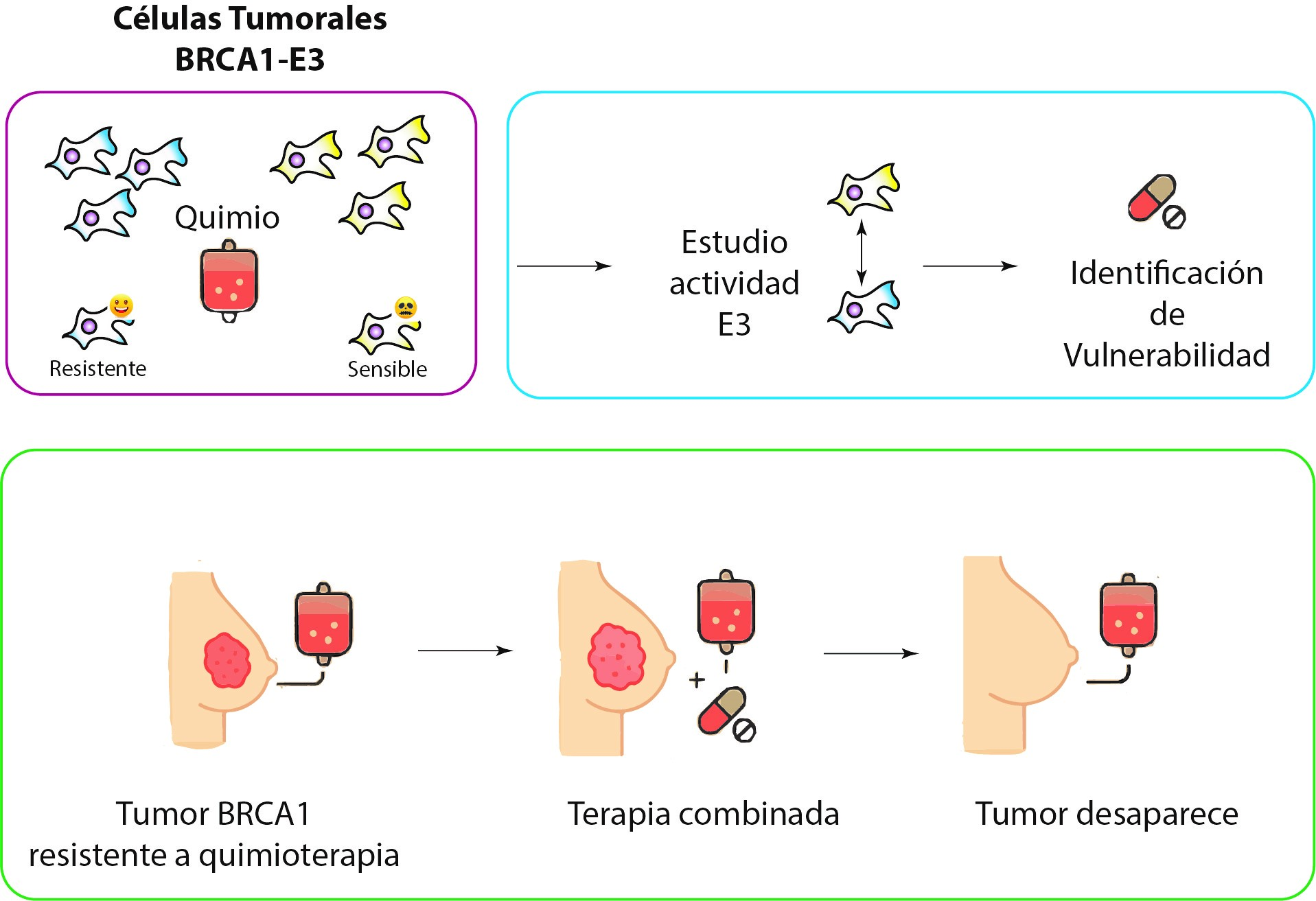

Although the BRCA1 gene has been known and studied for 30 years, the role of its E3 enzymatic activity remained controversial, and its relevance in cancer and DNA repair, or whether it was involved in other processes, had not yet been clearly determined. This is because there were no methods to directly study enzymatic activity within cells. All studies and conclusions were based on indirect observations, making it impossible to determine whether these observations were the result of defects in enzymatic activity or side effects, with contradictory results in many cases. However, it was clear that certain mutations that affected enzymatic activity and not the rest of BRCA1 predisposed individuals to the development of cancer, which was much more aggressive and resistant to chemotherapy.

In 2024, using a new technique developed by our research group, we deciphered the role and importance of E3 activity and saw that, while it is true that BRCA1 tumours deficient in E3 activity are resistant to the chemotherapy used in BRCA1 tumours, they do die with other alternative treatments.

In addition, other international research groups have described that certain BRCA1 tumour cells deficient in E3 SI activity are sensitive to chemotherapy. In this research project, we aim to apply our methods to understand why the lack of E3 activity makes some tumours sensitive to chemotherapy and others not. This will enable us to combine drugs to make all BRCA1 tumours deficient in E3 activity sensitive to chemotherapy.